Eero_Tuovinen \n\n\n

Eero_Tuovinen \n\n\nNow, Airk's been stirring up some discussion in the other thread about the old perennial, the "true nature" of 4th edition D&D. This directly inspired me to action. I'll note that this is not intended as a direct counter-point on anything Airk said about 4th edition; I do not really agree with him about the game's most optimal deployment (its true nature, if you will), and this description of my micro-campaign may serve to illustrate the differences, but mostly I just want to show you guys what, exactly, my current take on 4th edition is.

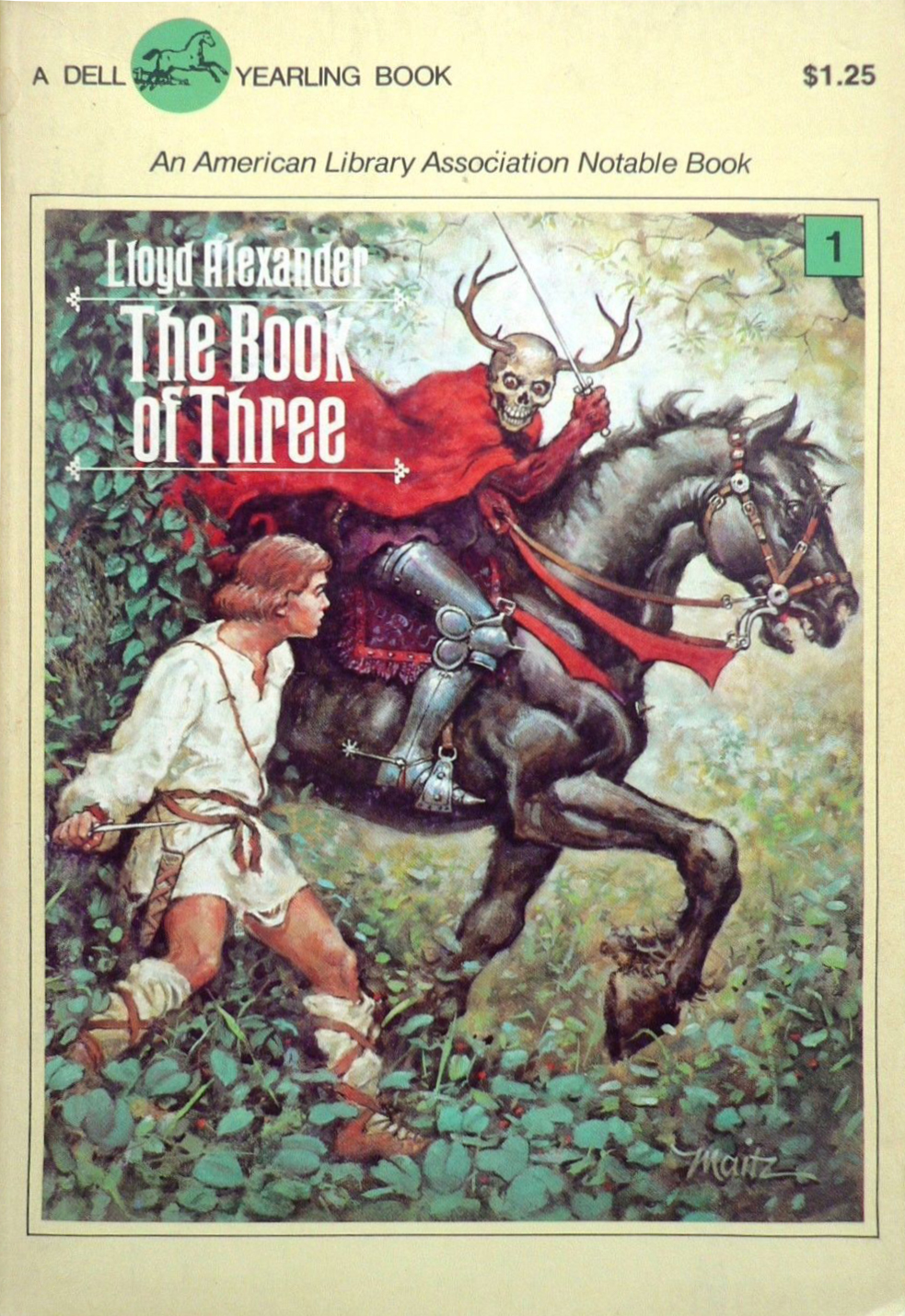

You might wish to check out our recent discussion about adaptations, because everything I say there about adapting prior works into roleplaying is in full force here, when I change a beloved fantasy classic into a miniatures skirmish wargame...

What's "Chronicles of Prydain"?

The premise of the Chronicles is that it's a fantasy epic drawing its inspiration from Welsh folklore: basically the same relationship that Marvel's Thor comics have with Norse myths. Prydain (an ancient name of Britain, that) is a political patchwork of petty kingdoms drawn together by the ever-weakening High Kingship, and threatened by the kingdom of Annuvin, the Land of the Dead, which has been stilted out of its cosmic role and immanenticized as a political force by Arawn, the undead king who deposed Achren the Enchantress as the ruler of the deadlands some time before the story begins. The Chronicles concern themselves with not only the resolution of the conflict between the living and the dead, but also with the growth of the humble pig-herd protagonist into the great hero of Prydain.

I chose Prydain for my 4th edition treatment because I wanted something that:

* I could relate to emotionally myself, getting excited about the story and characters and fantasy concepts.

* would be immediately intelligible to the players without me having to start the game with a crash-course in some weird literary niche they've never even heard of.

* would be trivially compatible with existing 4th edition materials; while I am all for full-body conversions of rpgs (that's what I usually do with D&D - rewrite the crunch from the ground up to fit the campaign), this was a small project and I wanted something that would fit with minor changes.

The 4th edition context

I've played something like maybe four or five sessions of 4th edition D&D myself (I'm counting the Gamma World variant as the same game for our purposes here). It's always been disastrously unfun: a lot of busywork in character creation followed by a shallow fictional presentation and one or two forced combat encounters. It's always ended in a total party kill, leaving us players to stare at each other in dumb disbelief: did we really just waste six hours on something so unsatisfying?

These test sessions of the game have always been lightly prepped and casual, which is obviously part of the reason for why the outcome has been like that. For instance, we've used various ready-made starter kit adventures and such, which in 4th edition's case happen to be famously borked. So no need for anybody to come explain to me that it's Keep on the Shadowfell that's bad and not 4th ed itself - I'm well familiar with the concept.

What I want now is a functional campaign basis for playing 4th edition without committing to a full campaign project (these are for me often multi-year affairs, big affairs). Gaining experience with a micro-campaign played pretty close to by-the-book seems like a good way to build up towards some more ambitious ideas I have.

The Plan

I'm a pretty analytical sort of person, so this prior context hasn't really convinced me to keep away from 4th edition; rather, it's motivated me to fix the game so that it starts working for me. (No disrespect intended towards those for whom the game works out of the box. I am famously a slow and clumsy GM, and a bone-headed player; I often need the game design itself to be clearer and more focused so I can play it successfully.) What I want 4th edition to be can be most succinctly expressed with a rpg theory witch chant:

Flavourful railroad princess play with embedded tactical skirmish challenges and formalized strategic layer.

I'll just leave that there in the assumption that it's clear enough for those who care. The key concern is that the game needs to be actually aesthetically flavourful, and that for me means abolishing practically everything 4th edition gives us in terms of literary content. It's all just much, much too vapid for me to work with. (Again, no offense intended: aesthetics are so very subjective, I'm glad if it works for you.) Thence, Chronicles of Prydain instead [grin].

It's also important to understand that while I don't think that the interactive strategic overlayer is mandatory for satisfying 4th edition play, I believe that it's an easy way to score player buy-in - including GM buy-in, frankly; I want to talk with the other players about the directions the railroad takes, and I want to have their input for setting up the skirmish combat scenes, and that implies bringing them in as strategic discussion partners.